Parsec is the Platform AbstRaction for SECurity, an open-source initiative to provide a common API to secure services in a platform-agnostic way. Parsec is a Cloud Native Compute Foundation Sandbox project.

Find here all the technical documentation of Parsec, alongside user and developer guides.

Go straight to the overview to learn more about the project!

Check out the Getting Started guides to quickly try out Parsec!

Then, depending on what you want to know, you can go to the users, client developers, service developers or security sections.

Don't hesitate to ask any question you would have when reading on our Community Slack Channel!

Parsec and all the repositories under the parallaxsecond organization are provided under

Apache-2.0. Contributions to this project are accepted under the same license.

Copyright 2019 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Welcome to Parsec

Parsec is the Platform AbstRaction for SECurity, a new open-source initiative to provide a common API to secure services in a platform-agnostic way.

Parsec aims to define a universal software standard for interacting with secure object storage and cryptography services, creating a common way to interface with functions that would traditionally have been accessed by more specialized APIs. Parsec establishes an ecosystem of developer-friendly libraries in a variety of popular programming languages. Each library is designed to be highly ergonomic and simple to consume. This growing ecosystem will put secure facilities at the fingertips of developers across a broad range of use cases in infrastructure computing, edge computing and the secure Internet of Things.

Why Platform-Agnostic Security?

Today's computing platforms have evolved to offer a range of facilities for secure storage and secure operations. There are hardware-backed facilities such as the Hardware Security Module (HSM) or Trusted Platform Module (TPM). There are firmware services running in Trusted Execution Environments (TEE). There are also cloud-based security services. At a bare minimum, security facilities may be provided purely in software, where they are protected by mechanisms provided in the operating system.

Over the years, software standards have emerged to allow developers to use these facilities from their applications. But these standards bring with them the following challenges:

- They are defined with the expectation that the caller is the "owner" of the platform, meaning that it has sole access to the underlying hardware. In reality, this is often not the case, because the caller might reside in a container or virtual machine, where it is sharing the host hardware with other applications. Existing software standards do not cater well for this situation.

- They are defined exhaustively, with lengthy specifications detailing all permissible operations and parameters. They are written from the perspective of the security device and its capabilities, rather than from the perspective of the application and its use case. This can offer a daunting and bewildering experience for developers, who spend a lot of time and effort figuring out how to map their use case onto the API. There is nothing to tailor the API so that it can be consumed easily for common, simple cases.

- They are specific to a programming language such as C. To consume them in other languages, it is necessary to use interoperability layers such as Foreign Function Interface (FFI), which can make the developer experience even more cumbersome and unnatural. Interoperability layers can also be a source of vulnerabilities.

- Standards tend to be adopted based on some knowledge of the target platform. So while it might be possible for code to be portable across multiple HSM vendors, for example, it is much harder to make code portable between an HSM-based platform and a TPM-based platform.

Parsec inverts this traditional approach to standardizing security interfaces, and it does so by putting applications front and center. It offers an API that is no less comprehensive, but it does so in a way that puts the needs of applications and their common use cases first.

Applications simply want the best-available security, and they want to be able to consume it in a way that is simple, natural, and hard to get wrong.

The following observations can be made about such applications:

- They can be written in a variety of programming languages.

- They may be written with no explicit knowledge of the hardware capabilities of the target platform, such as whether an HSM or TPM is available.

- They are often sharing the target platform hardware with other applications due to the use of virtualization or containerization technology.

- The secure assets owned by one application must be isolated from those owned by another. For example, private keys provisioned on a hardware device must be isolated such that only the provisioning application would be able to perform subsequent operations with those keys.

- They have differing requirements in terms of permissible cryptographic algorithms and key strengths.

These observations motivate the need for a new platform abstraction that offers a common palette of security primitives via a software interface that is both agnostic with respect to the underlying hardware capabilities, and also capable of supporting multiple client applications on the same host, whether those be within containers or within traditional virtual machines.

Parsec is a new software architecture and ecosystem that addresses this need.

Basis in Platform Security Architecture

Parsec is founded on the Platform Security Architecture (PSA). The PSA is a holistic set of threat models, security analyses, hardware and firmware architecture specifications, and an open source firmware reference implementation. The PSA provides a recipe, based on industry best practice, that allows security to be consistently designed in, at both a hardware and firmware level.

One of the provisions of the PSA is the PSA Crypto API. The PSA Crypto API is a comprehensive library of modern security primitives covering the following functional areas:

- Key provisioning and management

- Hashing

- Signing

- Message Authentication Codes (MAC)

- Asymmetric encryption

- Symmetric encryption

- Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD)

- Key derivation

- Entropy (random number generation)

A crucial characteristic of the PSA Crypto API is that applications always reference the keys opaquely, making it ideally suited to implementations where keys are provisioned within hardware and are never exposed.

The PSA Crypto API is defined in the C language. Parsec adopts the operations and contracts of the C API, and uses them as the basis for a language-independent wire protocol. Each operation is defined, along with all of its inputs and outputs, as a serializable contract, making it suitable to be invoked over an Inter-Process Communication (IPC) transport. Parsec maintains functional equivalence with the PSA Crypto API, but allows for out-of-process callers in any programming language.

The Parsec Service

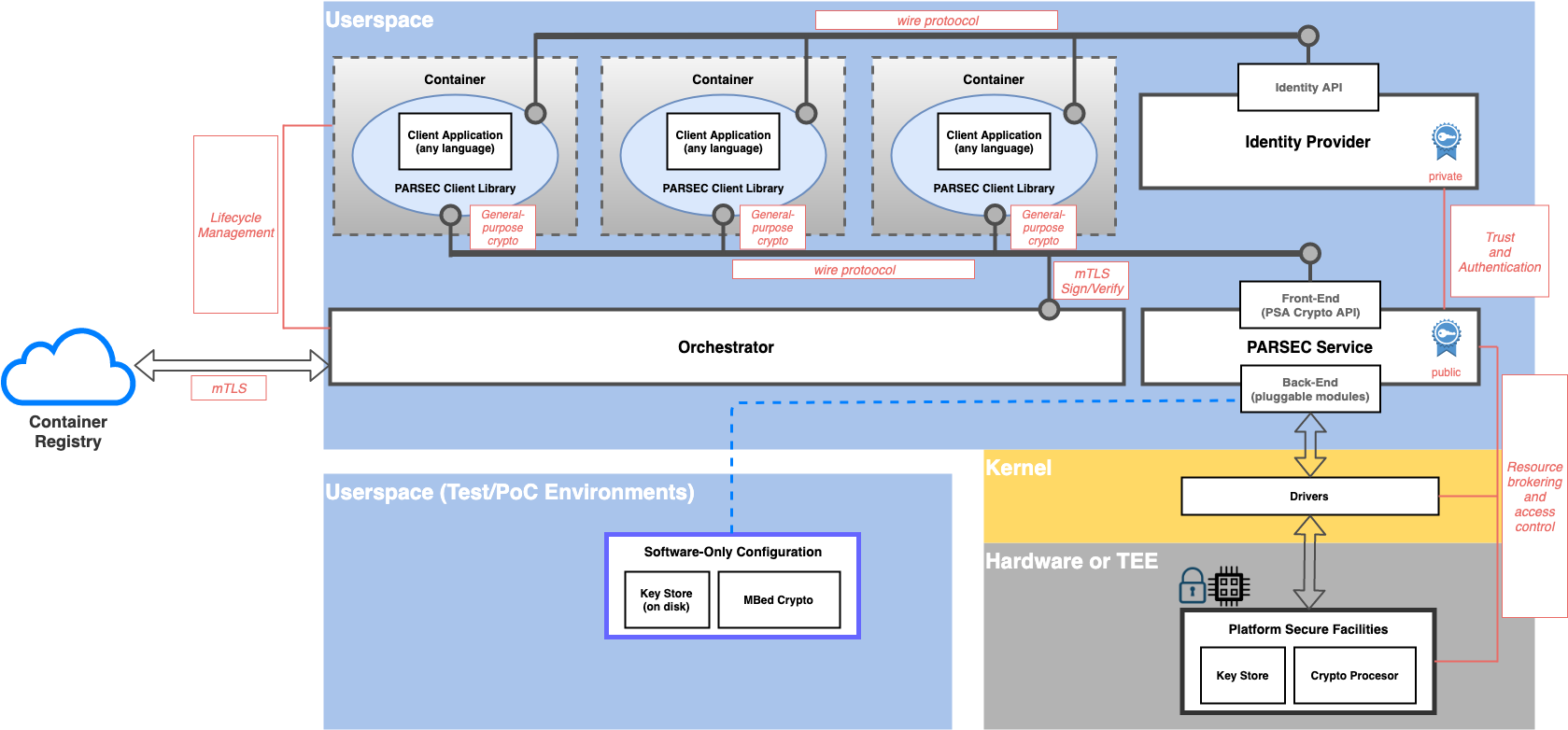

The core component of Parsec is the security service (or security daemon). This is a background process that runs on the host platform and provides connectivity with the secure facilities of that host and surfaces the wire protocol based on PSA Crypto.

The security service listens on a suitable transport medium. The transport technology is one of Parsec's many pluggable components, and no single transport is mandated. Choice of transport is dependent on the operating system and the deployment. On Linux-based systems where the client applications are running in containers (isolation with a shared kernel), the transport can be based on Unix sockets.

Client applications make connections with the service by posting API requests to the transport endpoint. This is usually done via a client library that hides the details of both the wire protocol and the transport. This is one of the ways in which the client library simplifies the experience of Parsec for application developers.

A single instance of the Parsec service executes on each physical host. In virtualized environments, the Parsec service may reside on a specially-assigned guest, or potentially within the hypervisor.

The security service does not support remote client applications. Each physical host or node must have its own instance of the service. However, it is possible for the service to initiate outbound remote calls of other services, such as cloud-hosted HSM services.

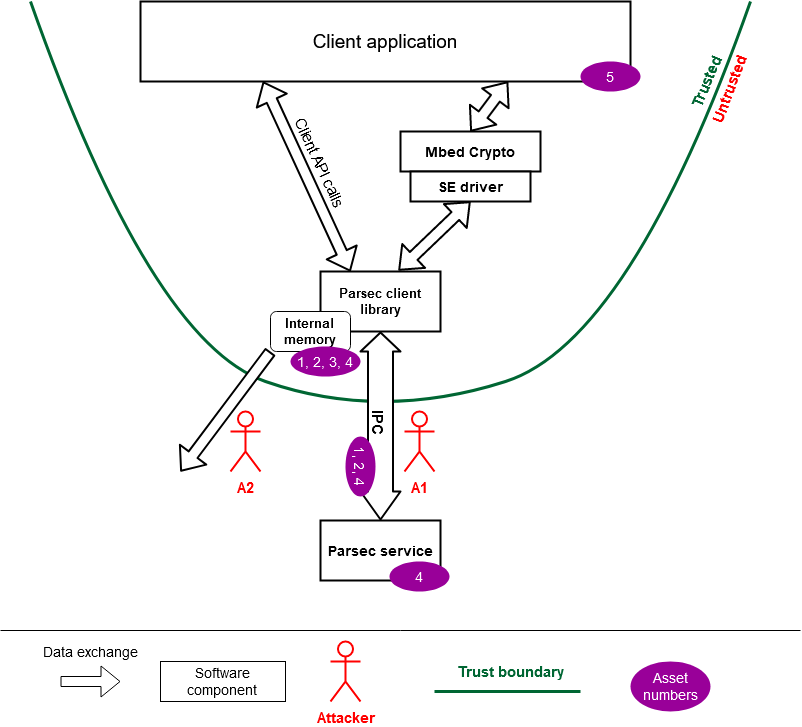

Multitenancy and Access Control

In addition to surfacing the common API, the Parsec service is also responsible for brokering access to the underlying security facilities amongst the multiple client applications. The exact way that this is done will vary from one deployment to another. (See the section below on pluggable back-end modules). Some of the brokering functionality may already reside in kernel drivers and other parts of the software stack. The Parsec service is responsible for creating isolated views of key storage and cryptographic services for each client application. The secure assets of one client must be kept protected from those of another.

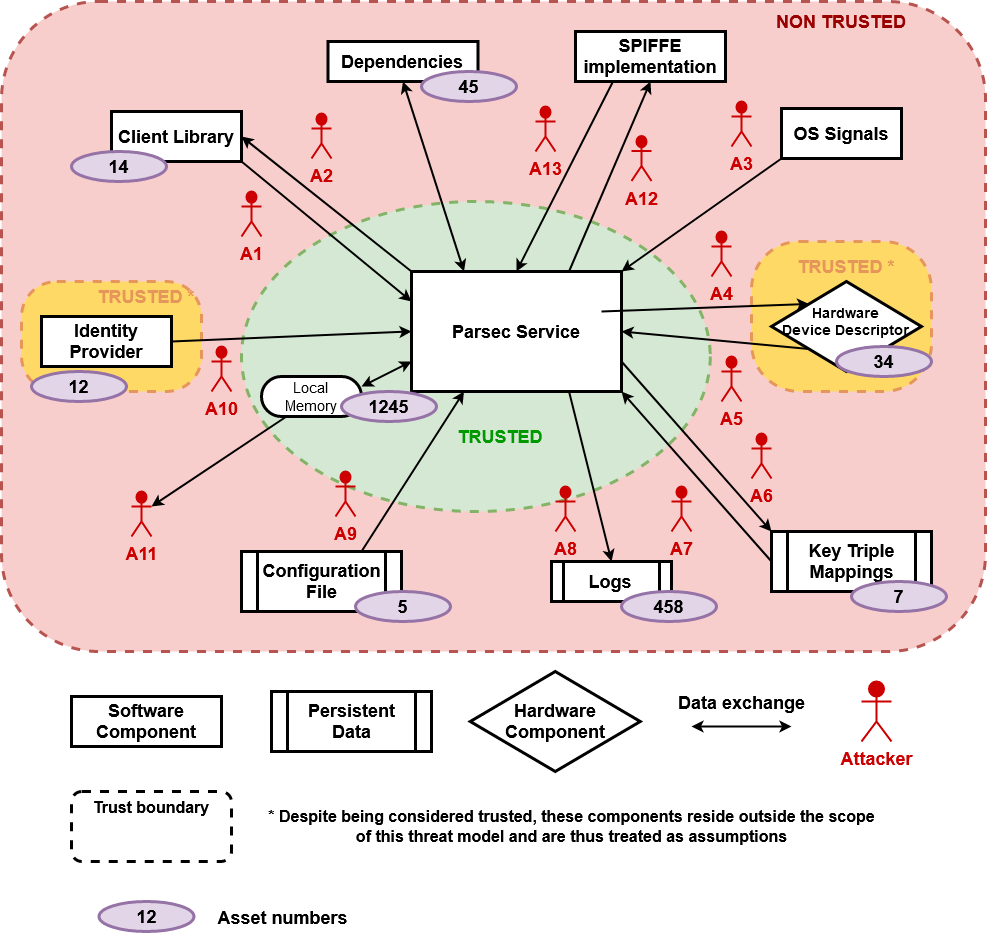

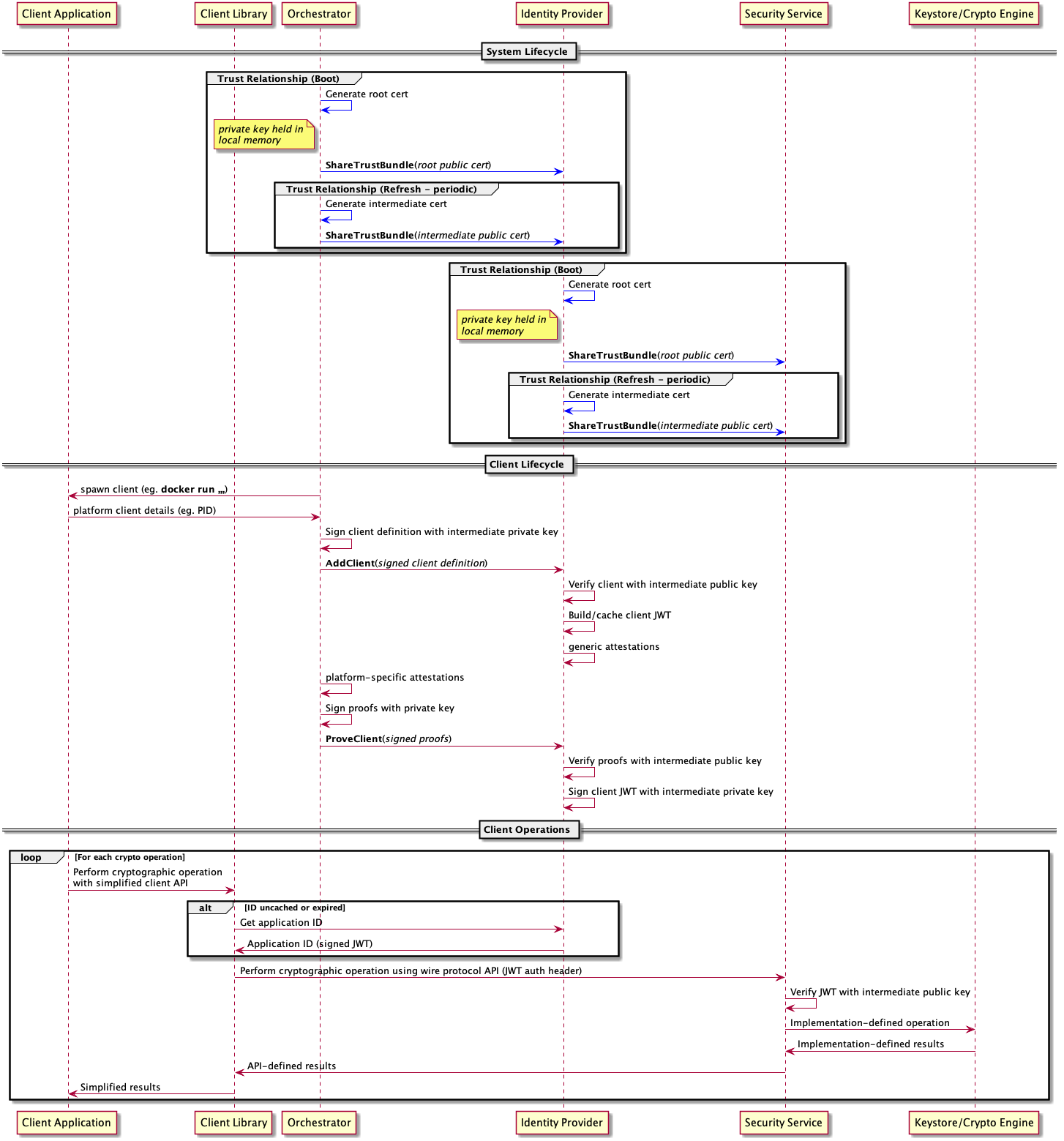

Central to this multi-tenant operation is the notion of application identity and the need for a separate identity provider service. A Parsec-enabled host must contain an identity provider service in addition to the Parsec service itself.

For more information about application identities and the identity provider, please refer to the system architecture document.

Pluggable Back-End Modules

The Parsec service employs a layered architecture, structured into a front-end and a back-end.

The front-end module provides the transport endpoint and listens for connections from clients. The front-end understands the wire protocol and the common API. It is responsible for serialization and de-serialization of the operation contracts.

The back-end modules are known as providers. An instance of the Parsec security service can load one or more providers. Providers implement the API operations using platform-specific or vendor-specific code. They provide the "last mile" of connectivity down to the underlying hardware, software or firmware.

For a deeper dive into the modular structure of the Parsec service, please take a look at the interfaces and dataflow design document.

Then delve into the source code to discover the back-end provider modules that exist. If you cannot find one that is compatible with the platform you intend to use, then please consider contributing a new provider.

Beautiful Client Libraries

A key aim of Parsec is to evolve an ecosystem of developer-friendly client libraries in multiple programming languages.

Parsec avoids the cumbersome, auto-generated language bindings that are so often a part of standardized interfaces.

Parsec's client libraries are beautiful.

Each client library is carefully crafted to follow the idioms of the language that it targets. Consuming a Parsec client library will always feel natural to a developer who works in that language. Everything from naming conventions to object lifecycle will be blended to create a highly-idiomatic developer experience.

But Parsec's focus on developer ergonomics goes further than this. Parsec's client interface is filled with conveniences to eliminate complexity unless complexity is required. The Parsec API is functionally equivalent with the PSA Crypto API, and none of this functional completeness is lost in the client layer. All possible variants of key type and algorithm type are exposed in case they are needed. But the client library offers smart default behaviors so that simple use cases can be achieved with very little code. Parsec enables client code to be small and elegant. And even if it needs to be less small, it should still be elegant.

Source Code Structure

Parsec is composed of multiple code repositories. For more information about how the code in the repository is organized, please see the source code structure document.

Copyright 2019 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Getting Started With Parsec

Welcome!

Welcome to the Parsec Getting Started guide. Take a look through the headings below and follow the links that best describe what you would like to do.

I Want to Check if Parsec is Running

The installation guide includes a quick method that you can use to see if Parsec is already installed and running on your system.

I Want to Install the Parsec Service

There are a few different ways to get the Parsec service up and running on your system. You may be able to install via your package manager, or use a different method. Go here to check out your installation options.

I Want to Use Parsec API's in My Own Code

You can consume Parsec API's in several programming languages. You can learn how to do this here.

I Want to Use Parsec from the Command Line

Take your first steps with Parsec using the command-line parsec-tool. Follow our familiarization

guide to learn how to use the tool to check the service configuration, create

key pairs, sign/decrypt messages and create certificate requests.

I Want to Understand How Parsec Works Internally

If you want to understand the internal details of Parsec, including the structure of the project source code, then the best place to start is the service developer guide.

I Want to Create a New Parsec Client Library

Fantastic! Parsec client libraries in new programming languages are always welcomed by the maintenance team and the community. Head over to the client developer guide and learn how to get started.

I Want to Make Sure that My Parsec Installation Is Secure

Read the procedure for creating secure installations to learn the steps for setting up a secure deployment. If you have installed Parsec using a package manager, then these steps should already have been followed by the installation scripts on your system, and there should be nothing more to do. However, you can also use the secure deployment guide to ensure that your system is installed according to best practices.

I Want to Configure the Correct Hardware Back-End for My Device

Parsec back-end modules are known as providers. Default installations of Parsec use a software-based provider, also known as the Mbed provider, which is very simple to use but does not integrate with the secure hardware that you might have on your device. Follow the configuration guide to learn how to edit Parsec's configuration file to select the right kind of provider. You can also learn how to set up and use the different providers here.

If you are not sure how your Parsec service is configured, or whether it is using a hardware back-end, the command-line tooling guide has some steps to help you check this.

I Want to Get Involved With the Parsec Community

We will be delighted to have you! Head over to our community repository to discover how to join and contribute to the Parsec conversation on Slack, Zoom and GitHub.

Copyright 2021 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Quickstart for Linux on x86

This content has moved to the installation guide.

Copyright 2022 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Quickstart for openSUSE and SUSE

This content has moved to the installation guide.

Copyright 2021 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Docker

Please refer to the installation guide.

Copyright 2021-2023 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Installation Options

Is Parsec Already Running?

The easiest way to check whether Parsec is already installed and running on your system is to open a terminal window and issue this command:

parsec-tool ping

If the Parsec components are installed and running, this command will produce output similar to the following:

[INFO] Service wire protocol version

1.0

If this fails, then do not worry. Read on to learn the best way to get Parsec up and running on your system.

Option 1: Install Parsec Using the Package Manager

The easiest way to install Parsec is by using the package manager on your system. Parsec is available as a package in Fedora and openSUSE Linux distributions. If you are using one of these distributions, follow the guide below to get Parsec installed and working.

Installing the Parsec Packages

To install Parsec on openSUSE Tumbleweed or openSUSE Leap 15.3 (and later), just install

parsec and parsec-tool from YaST (graphical UI), or from zypper (command line):

sudo zypper install parsec parsec-tool

Note: If you use SUSE SLE15-SP3 (or later), parsec and parsec-tool are available from

Package-Hub repository. So, please enable Package-Hub before trying to install those packages.

To install Parsec on Fedora 34 (and later), you can run the following command from the terminal:

sudo dnf install parsec parsec-tool

Setting Up User Permissions

When you install Parsec with the package manager (on either openSUSE or Fedora), the package

installation scripts will include the creation of a parsec-clients user group. Client applications

that wish to use the Parsec service should first be made members of this group, otherwise they will

be denied permission to access the service endpoint. To make your current user a member of

parsec-clients, issue this command:

sudo usermod -a -G parsec-clients $USER

Please note that this change will not be applied immediately within your current terminal window. To ensure that these changes take effect, you can either log out and log back in as the same user, or you can forcibly apply the changes using this command:

newgrp parsec-clients

To ensure that the current user is a member of the parsec-clients group, use this command:

groups

and ensure that parsec-clients is in the list of groups.

Starting the Parsec Service

When you install Parsec with the package manager, it will be installed as a system service. Use the following command to start the service immediately, and also ensure that it is enabled for automatic start on subsequent system boot:

sudo systemctl enable --now parsec.service

Checking the Installation

To check that the installation is functional, issue this command:

parsec-tool ping

If the Parsec components are correctly installed and running, you should see output similar to the following:

[INFO] Service wire protocol version

1.0

If instead you see an error message, go back through the above steps and ensure that the service was

started, and that your current user is a member of the parsec-clients group.

Option 2: Download a Quick-Start Release

If you are using a system that does not support installing Parsec through the package manager, you can get familiar with Parsec by downloading the latest release from GitHub and running it manually as a quick-start package. This is currently supported for any 64-bit Linux system running on the x86 architecture.

Note: this method is suitable for familiarization and experimentation only. Do not use this method in production environments. To securely install Parsec on Linux for production, check this guide instead.

Check that Your System is Suitable

To download a pre-built release of Parsec, you need to be running a 64-bit Linux system on the x86

architecture, and you need to have at least version 2.27 of the Gnu C Library (GLIBC), which you

can check by running the following command:

ldd --version

Download the Latest Quick-Start Release Bundle

Run the following command to download and unpack the quickstart-1.4.0-linux-x86_64 folder.

curl -s -N -L https://github.com/parallaxsecond/parsec/releases/download/1.4.0/quickstart-1.4.0-linux-x86_64.tar.gz | tar xz

The resulting directory contains the following structure

quickstart-1.4.0-linux-x86_64

├── bin

│ ├── parsec # The parsec binary

│ └── parsec-tool # The parsec client tool

└── quickstart

├── README.md # Quickstart README

├── build.txt # Information about the Parsec build environment

├── config.toml # The config file used by parsec

└── parsec-cli-tests.sh # Standard parsec-tool tests

The following examples assume you've navigated to the quickstart-1.4.0-linux-x86_64/quickstart

directory, so let's do that now.

cd quickstart-1.4.0-linux-x86_64/quickstart

Configure Your Environment

Calls to the parsec-tool assume that the environment variable PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT has been

set to the path for the socket created by the parsec process. By default, that socket is placed in

the directory where you've executed the parsec command, so we can configure that variable as such

export PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT=unix:$(pwd)/parsec.sock

It may also be helpful to add the bin directory to your path. The examples below assume that this

has been done.

export PATH=${PATH}:$(pwd)/../bin

Start the Parsec Service

Start the Parsec service with this command:

parsec &

You should see some lines of console output as the service starts, ending with the following:

[INFO parsec] Parsec is ready.

Using the Parsec Tool

You can now use the parsec-tool to check that the service is running:

parsec-tool ping

If the Parsec components are correctly downloaded and running, you should see output similar to the following:

[INFO] Service wire protocol version

1.0

Controlling the Service Manually

When using the Parsec service as a pre-built download, it will not be installed as a system service. Therefore, to stop the service, issue the following command:

pkill parsec

You should see some lines of output ending with:

[INFO parsec] Parsec is now terminated.

You can also cause the service to restart, which can be useful if you have made some configuration changes for example. This command will cause the service to reload its configuration and restart:

pkill -SIGHUP parsec

Again, this will produce some lines of output, and the final line will be:

[INFO parsec] Parsec configuration reloaded.

Running the Test Script

The quick-start bundle also contains the parsec-cli-tests.sh testing script, which executes a

simple set of tests to ensure that the Parsec service is operating correctly. Some of these tests

use the local openssl installation as a point of comparison, ensuring that Parsec's results are

equivalent to those expected by openssl.

As this script uses the parsec-tool, the PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT environment variable needs to

be set as follows:

export PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT="unix:$(pwd)/parsec.sock"

If parsec-tool is not installed into a directory included in PATH, then you also need to define

the PARSEC_TOOL environment variable with a full path to it. Assuming the current working

directory is quickstart-1.4.0-linux-x86_64/quickstart:

export PARSEC_TOOL="$(pwd)/../bin/parsec-tool"

To run the script from the same directory, simply execute it without any arguments as follows:

./parsec-cli-tests.sh

The script will run a sequence of operations and produce output along the following lines:

Checking Parsec service...

[INFO ] Service wire protocol version

1.0

Testing Mbed Crypto provider

- Test random number generation

[DEBUG] Parsec BasicClient created with implicit provider "Mbed Crypto provider" and authentication data "UnixPeerCredentials"

[INFO ] Generating 10 random bytes...

[DEBUG] Running getuid

[INFO ] Random bytes:

A6 F5 90 24 DF FF 50 1F 29 2E

....

The parsec-cli-tests.sh script also accepts some command-line parameters to adjust its behavior.

You can use the -h option to get additional help on these.

Note: If openssl is not installed into a directory included in PATH then you also need to

define OPENSSL environment variable with a full path to it:

export OPENSSL="<full path>/openssl"

Option 3: Use a Quickstart Docker Image

If you'd like to isolate your quickstart experience to a temporary Docker container, you can get familiar with Parsec by utilizing a pre-built image available on ghcr.io. This is currently supported for any system able to run 64-bit Linux x86 Docker images.

Note: this method is suitable for familiarization and experimentation only. Do not use this method in production environments. To securely install Parsec on Linux for production, check this guide instead.

Check that Your System is Suitable

To run a Docker container, you need to have Docker installed on your system. If you do not, you follow the instructions at https://docs.docker.com/get-docker to install Docker.

Run the Latest Quick-Start Release Image

Run the following command to pull and run the Parsec quickstart image.

docker run --rm --name parsec -it ghcr.io/parallaxsecond/parsec-quickstart bash

This will start the parsec-quickstart image and place you into the /parsec/quickstart directory.

The /parsec directory has the following structure

/parsec

├── bin

│ ├── parsec # The parsec binary

│ └── parsec-tool # The parsec client tool

└── quickstart

├── README.md # Quickstart README

├── build.txt # Information about the Parsec build environment

├── config.toml # The config file used by parsec

└── parsec-cli-tests.sh # Standard parsec-tool tests

The following examples assume you're running from within the /parsec/quickstart directory.

Configure Your Environment

The container's environment has already been configured for easy usage. You should not need to do anything else to configure the environment.

PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT=unix:/parsec/quickstart/parsec.sock

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/parsec/bin

Start the Parsec Service

Start the Parsec service with this command:

parsec &

You should see some lines of console output as the service starts, ending with the following:

[INFO parsec] Parsec is ready.

Using the Parsec Tool

You can now use the parsec-tool to check that the service is running:

parsec-tool ping

If the Parsec components are running, you should see output similar to the following:

[INFO] Service wire protocol version

1.0

Controlling the Service Manually

When using the Parsec service as a pre-built download, it will not be installed as a system service. Therefore, to stop the service, issue the following command:

pkill parsec

You should see some lines of output ending with:

[INFO parsec] Parsec is now terminated.

You can also cause the service to restart, which can be useful if you have made some configuration changes for example. This command will cause the service to reload its configuration and restart:

pkill -SIGHUP parsec

Again, this will produce some lines of output, and the final line will be:

[INFO parsec] Parsec configuration reloaded.

Running the Test Script

The quick-start image also contains the parsec-cli-tests.sh testing script, which executes a

simple set of tests to ensure that the Parsec service is operating correctly. Some of these tests

use the local openssl installation as a point of comparison, ensuring that Parsec's results are

equivalent to those expected by openssl. The image has a valid version of openssl installed.

To run the script, simply execute it from the /parsec/quickstart directory without any arguments

as follows:

./parsec-cli-tests.sh

The script will run a sequence of operations and produce output along the following lines:

Checking Parsec service...

[INFO ] Service wire protocol version

1.0

Testing Mbed Crypto provider

- Test random number generation

[DEBUG] Parsec BasicClient created with implicit provider "Mbed Crypto provider" and authentication data "UnixPeerCredentials"

[INFO ] Generating 10 random bytes...

[DEBUG] Running getuid

[INFO ] Random bytes:

A6 F5 90 24 DF FF 50 1F 29 2E

....

The parsec-cli-tests.sh script also accepts some command-line parameters to adjust its behavior.

You can use the -h option to get additional help on these.

Option 4: Build from Source Code

If the above installation options are not suitable, please refer to the instructions for building from source code and secure installation on Linux.

The Parsec video tutorial series demonstrates the full set of steps needed to build Parsec from source code on a Raspberry Pi, and is applicable to similar Linux systems.

Option 5: Include Parsec in a Custom Embedded Linux Distribution using Yocto Project

If you are building a Yocto-based custom Linux distribution and you wish to include Parsec in your image, refer to the documentation for the meta-parsec layer.

Copyright 2022 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Using Parsec from the Command Line

Introduction

Many useful Parsec operations can be performed using Parsec's command-line tool, known as

parsec-tool. The tool can be useful when you need to perform administrative steps in order to

integrate Parsec with another component in your system. Such integrations might require the creation

of a key pair or a certificate request, for example. You can also use the parsec-tool in your

shell scripts when you need to automate seqeuences of operations for key management and

cryptogpraohy. Use this short guide to get familiar with basic use of the most common operations.

Installing the Parsec Command-Line Tool

To use this guide, you need to have parsec-tool installed or built.

For installing, use the following command:

cargo install parsec-tool

For building it, use the following commands:

git clone https://github.com/parallaxsecond/parsec-tool.git

cd parsec-tool

cargo build

To run the example commands in this guide, you will also need to ensure that the parsec-tool

application is available on your $PATH. If you installed the tool using a package manager, then

this will happen automatically. If you downloaded a binary or built the tool yourself from source

code, you may need to modify your $PATH, or copy the parsec-tool application into a folder that

is already searched.

Before proceeding, ensure that you can run parsec-tool from your shell or terminal window as

follows:

parsec-tool

This should display a help summary.

Checking the Version

The following command will display the version number for the parsec-tool installation that you

are using:

parsec-tool --version

You normally don't need to worry about the version. Parsec is designed with a robust protocol

between client applications and the service. It should be possible for any version of the

parsec-tool to work with any other version of the Parsec service. However, running an older

version of the parsec-tool might mean that some commands are unavailable.

Getting Help With Commands

This document does not contain detailed man pages for all of the commands. We hope to be able to

make man pages for parsec-tool available online in the future. For the time being, you can use the

tool itself to generate help text for the available operations.

To generate a help summary for the tool as a whole, simply invoke parsec-tool without any

arguments, or with the --help argument. This will display the summary help text, which includes a

list of all available commands.

To get more detailed help text for a specific command, use the --help option for that command. For

example, to get help text for the create-rsa-key command, you would type:

parsec-tool create-rsa-key --help

This will provide a full help text for the command, including documentation for all of the command-line parameters that this command accepts.

Setting the Service API Endpoint

Parsec uses a Unix domain socket to carry commands and responses between client applications and the

service. Since parsec-tool is a Parsec client application, it also uses this domain socket to send

commands to the service. By default, the Parsec domain socket has a full path of

/run/parsec/parsec.sock. The parsec-tool will expect to find the socket endpoint at this

location.

If your service configuration has been modified to use a non-default socket path, then you will need

to tell the parsec-tool to find the socket at its correct place. Set the environment variable

PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT in your shell before using the parsec-tool as follows:

export PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT=unix:/correct/path/to/parsec/endpoint/parsec.sock

Pinging the Service

Before running any other operations, it is useful first to check that the Parsec service is running

and healthy. To use the parsec-tool, you type parsec-tool, followed by the name of the command

that you want to run, followed by any additional arguments that are needed by that specific command.

The ping command is the simplest command, and it doesn't require any additional arguments:

parsec-tool ping

If the service is running and healthy, you will see output as follows:

[INFO] Service wire protocol version

1.0

If you see this message, your Parsec service is running and responding normally, and you can proceed with the other examples in this guide.

If you don't see this message, check the troubleshooting steps below.

- If you see the error

parsec-tool: command not foundit means thatparsec-toolis either not installed or cannot be found in any of the directories on your$PATH. Check the installation guide to learn how to obtain theparsec-tooland to ensure that it can be found. - The fault message

[ERROR] Error spinning up the BasicClient: the socket address provided in the URL is not validmight be seen. This might mean thatparsec-toolis trying to locate the service API endpoint at the wrong location. By default,parsec-toolexpects the Parsec service endpoint to be/run/parsec/parsec.sock. If your Parsec service is using a different endpoint, then you need to set thePARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINTenvironment variable to the correct path. See the section above on setting the endpoint. Another cause of this error might be that your current user is not a member of theparsec-clientsgroup. When you install Parsec using a package manager, the package scripts normally createparsec-clientsgroup, and only users who are members of this group are allowed to contact the service endpoint. Use thegroupscommand to list the groups that your current user is a member of, and refer to the installation guide for help on setting the correct permissions.

If these steps do not help, the Parsec community may be able to assist you. We are always very happy to hear from users with your questions and queries. Head over to the community repo to learn how to get in touch via Slack and Zoom.

Checking the Service Back-End Configuration

The parsec-tool includes commands that can help you check on how the service has been set up.

These checks can be useful, for example, if you wish to make sure that the Parsec service is using

the correct secure hardware on your device, such as your Trusted Platform Module (TPM) or Hardware

Security Module (HSM).

To check the hardware back-end configuration of Parsec on your device, run this command:

parsec-tool list-providers

This command displays a list of the back-end provider modules that have been activated in the Parsec service. The entry at the top of this list is the most important one, because this entry tells you which back-end provider will be used by default. You should pay particular attention to this entry, and ensure that it matches your expectations for how Parsec has been integrated with your device hardware.

If you are experimenting or prototyping with Parsec in a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) or non-production environment, you will probably be using the software back-end (also known as the Mbed Crypto or Mbed TLS back-end). This is the back-end provider that is configured out of the box in new Parsec installations. It will appear in the list as follows:

ID: 0x01 (Mbed Crypto provider)

Description: User space software provider, based on Mbed Crypto - the reference implementation of the PSA crypto API

Version: 0.1.0

Vendor: Arm

UUID: 1c1139dc-ad7c-47dc-ad6b-db6fdb466552

If you are using this back-end, then you should be aware that it does not offer any specific security features. This back-end provider is suitable for evaluation and experimentation only.

For Parsec to be integrated with a hardware or firmware TPM on your device, the topmost back-end provider should be the TPM provider, which will appear as follows:

ID: 0x03 (TPM provider)

Description: TPM provider, interfacing with a library implementing the TCG TSS 2.0 Enhanced System API specification.

Version: 0.1.0

Vendor: Trusted Computing Group (TCG)

UUID: 1e4954a4-ff21-46d3-ab0c-661eeb667e1d

For Parsec to be integrated with a hardware module using the PKCS#11 interface, the topmost entry should be:

ID: 0x02 (PKCS #11 provider)

Description: PKCS #11 provider, interfacing with a PKCS #11 library.

Version: 0.1.0

Vendor: OASIS Standard.

UUID: 30e39502-eba6-4d60-a4af-c518b7f5e38f

For hardware accessed through a CryptoAuthLib interface, the entry should be:

ID: 0x05 (CryptoAuthentication Library provider)

Description: User space hardware provider, utilizing MicrochipTech CryptoAuthentication Library for ATECCx08 chips

Version: 0.1.0

Vendor: Arm

UUID: b8ba81e2-e9f7-4bdd-b096-a29d0019960c

For Parsec to integrate with a PSA root-of-trust implementation via the Trusted Services project, the entry should be:

ID: 0x04 (Trusted Service provider)

Description: Software exposing functionality provided by the Crypto Trusted Service running in a Trusted Execution Environment

Version: 0.1.0

Vendor: Arm

UUID: 71129441-508a-4da6-b6e8-7b98a777e4c0

In all configurations, there will be a final entry in the list that reads as follows, indicating the core back-end that is always enabled for administrative operations:

ID: 0x00 (Core Provider)

Description: Software provider that implements only administrative (i.e. no cryptographic) operations

Version: 0.8.0

Vendor: Unspecified

UUID: 47049873-2a43-4845-9d72-831eab668784

You can learn more details about the different Parsec back-end providers here.

Checking the Service Front-End Configuration

The Parsec service includes front-end configuration modules known as authenticators. These are used to ensure that the operations of multiple client applications are kept separate from one another. Parsec authenticator modules contain logic to decide on the identity of any client application that is using the service. Client applications of any given identity will each have their own namespace, which means that any named keys that they create will be visible only to them, and never to other client applications.

The following command can be used to display the authenticator mechanism that is in use:

parsec-tool list-authenticators

By default, this command will output the following:

[INFO ] Available authenticators:

ID: 0x03 (Unix Peer Credentials authentication)

Description: Uses Unix peer credentials to authenticate the client. Verifies that the self-declared Unix user identifier (UID) in the request's authentication header matches that which is found from the peer credentials.

Version: 0.1.0

This message means that Parsec will use the Unix user identifier of each client process as the scope of the namespace. Any client applications that run as the same Unix user will be considered the same client, and will see the same set of created keys. Client applications running as different Unix users will likewise see different sets of keys.

It is also possible for client applications to be differentiated based on a SPIFFE identity. If authentication has been configured in this way, then the command output will look as follows:

[INFO ] Available authenticators:

ID: 0x04 (JWT SPIFFE Verifiable Identity Document authentication)

Description: Authenticator validating a JWT SPIFFE Verifiable Identity Document

Version: 0.1.0

The final supported method is known as Direct Authentication. This method is not recommended for production environments, but it can be used for evaluation. In this mode, the Parsec service will allow each client application to declare its own identity as a simple string, which will not be validated in any way. Client applications need to trust each other to use distinct strings in a sensible way. When this method is configured, the command output will read as follows:

[INFO ] Available authenticators:

ID: 0x01 (Direct authentication)

Description: Directly parses the authentication field as a UTF-8 string and uses that as the application identity. Should be used for testing only.

Version: 0.1.0

You can learn more details about the different Parsec front-end authenticators here.

Signing with an Elliptic Curve Key

Let's learn how to create an Elliptic Curve (EC) key pair in Parsec, and use it to sign a message. Create an EC key pair with the default curve and settings as follows:

parsec-tool create-ecc-key --key-name my-ecc-key

This command will produce the following output:

[INFO ] Creating ECC signing key...

[INFO ] Key "my-ecc-key" created.

You can also use the list-keys command:

parsec-tool list-keys

This will list the key that you just created, in addition to any others that have been created by the same client:

* my-ecc-key (Mbed Crypto provider, EccKeyPair { curve_family: SecpR1 }, 256 bits, permitted algorithm: AsymmetricSignature(Ecdsa { hash_alg: Specific(Sha256) }))

You can export the public part of the key using the export-public-key command:

parsec-tool export-public-key --key-name my-ecc-key

This will output the public part of the key in PEM format, similar to the output shown below:

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MFkwEwYHKoZIzj0CAQYIKoZIzj0DAQcDQgAEt6IxxREfORO2+Se/4AlBQQDpPydx

JymgCiCUi6A6w+lYVGLy8W9HWSSC8fQwgRvDTWmQc6zJLl59XizBEtNlMQ==

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

To sign a simple plaintext messsage with this key, use the sign command:

parsec-tool sign --key-name my-ecc-key "Hello Parsec"

This command will automatically hash the message with the SHA-256 algorithm and then ask the Parsec service to use the private key to sign the hash. The resulting signature will be shown in a base-64 encoding:

[INFO ] Hashing data with Sha256...

[INFO ] Signing data with Ecdsa { hash_alg: Specific(Sha256) }...

MEUCIDZz+ywOKc8kyst5DlJ9GZ9TPpeMXUD3xeTolwp9fENMAiEAxCYfOHt2jvtkz2SpXdo2IYuBjlht9DX+lXorpGcAU5U=

Signing with an RSA Key

We can use RSA keys for digital signatures. The following command will create a new RSA key pair and set its purpose as a signing key:

parsec-tool create-rsa-key --key-name my-rsa-signing-key --for-signing

This will create an RSA signing key of the default key strength, which is 2048 bits. You can use the

list-keys command to check that this key was created:

parsec-tool list-keys

This will list the key that you just created, in addition to any others that have been created by the same client:

* my-rsa-signing-key (Mbed Crypto provider, RsaKeyPair, 2048 bits, permitted algorithm: AsymmetricSignature(RsaPkcs1v15Sign { hash_alg: Specific(Sha256) }))

You can export the public part of the key using the export-public-key command:

parsec-tool export-public-key --key-name my-rsa-signing-key

This will output the public part of the key in PEM format, similar to the output shown below:

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEA4+XKkuDB9p06E/oxKHmK

Pzh58/eEQLZL9rTetOGxSJoruFAinC13zn76KHQfLYRYZhoFbXDdel/LHxHzVNB2

0LIrcQ8+3Sk2BZMyAUReCxV9IZ/3L4yrbbCaJCWSrK20KVjIgoymhBZhwbqKmM2s

rqGZZ3ZHAe+9bphQKjcFoooDQyzk6XNY3TM2PFYsRt41Q+u+4Dcp/Jusi1cv5Cij

hfvJV41yUV8I24H0GkQiJDidH/OdSiVytBZb7G7sfjwlPP3x3BB5hfE56QShNjWk

23ko0a1vgE8vIIlXNfQ/HjEgYPst0YmeJpPb/eSeWTPjxOYyfLn6d2XoS7gjsZwG

CwIDAQAB

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

To sign a simple plaintext message with this key, use the sign command:

parsec-tool sign --key-name my-rsa-signing-key "Hello Parsec"

This command will automatically hash the message with the SHA-256 algorithm and then ask the Parsec service to use the private key to sign the hash. The resulting signature will be shown in a base-64 encoding:

[INFO ] Hashing data with Sha256...

[INFO ] Signing data with RsaPkcs1v15Sign { hash_alg: Specific(Sha256) }...

O6VLgOT3pXDqvJi7faUguDvpKIfoQw4r8XlIgFn+gBOlTkW2nBmyHJyi8UU3RIo7f2AF5P9g+8MY4RKbADFSl7446iew4CjkZxWe+5M2sbYEKVZ+wGdhvWQRGXDeo5foW7TqqbdMU4i0tRp9tnq5GcXtpNgTAhtajWTuAnNgEv7IQHypeOgOomfK80q9P4wVbRvS9RCfE6tsyVikT8QgIUDYQjnY7inn4tW1a5HsFTVP4rSy2htHLgS/l9FLxW6ZyTXfdWF33zpNoGrmVx7IU0HapFiIgIBmBuNVq3gelQiXRAXK5mYEJvkLvba7TiAJJMUDQc/uKSY7GUAMh/SCZQ==

Encryption with an RSA Key

We can use RSA keys for asymmetric encryption and decryption. Encryption is performed using the public key, while decryption uses the private key.

Create an RSA key pair for encryption as follows:

parsec-tool create-rsa-key --key-name my-rsa-enc-key

Use the list-keys command to check that the key exists:

parsec-tool list-keys

The output will include a line for the key that you just created, similar to the following:

* my-rsa-enc-key (Mbed Crypto provider, RsaKeyPair, 2048 bits, permitted algorithm: AsymmetricEncryption(RsaPkcs1v15Crypt))

Export the public part of the key using the export-public-key command:

parsec-tool export-public-key --key-name my-rsa-enc-key

This command will output the public key in PEM format as follows:

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAtfeDG1fFd88koc1Fcksi

X17fkm4U2ljLOHaBSSpWaSoBWo2dMRUtzF+Ijogt9DhR2bv3ej7BLGN6DF1YDVGb

M+6bkzD7vSXkT45fe2FYn+86nBpG4znsJBBmQoH19YNTXF7MSxiq2WTVyJfikSTV

/r2bQzHFTkMh0iTPJlfx0et9JSTltK2ApZ6tWiKJX0Kw2kNw2iCKUmLqNGxc8XM2

H6sk0I24M0VpIMWy6c8W2z7TnhvogD32ct+AiJtCwqqo0gMQKgvOHSTctys5i1pE

3ozcS/smaWhYTVPZLUK3bBgA7XaXD37FzLu6qhRCyv/DdrhwcqvIYWtOo2d0pvSO

/wIDAQAB

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

For convenience, you can use the parsec-tool to encrypt a simple plaintext message using the

public key:

parsec-tool encrypt --key-name my-rsa-enc-key "secret message"

The ciphertext will be output as a base-64 encoding:

[INFO ] Encrypting data with RsaPkcs1v15Crypt...

ivk6yCKxFlIXRaQkfI5SrvhJtVXUz2VoXwC2xK7zU6UG1w0LNk7ZScz1pgpghc0IgftjjvhzK+6R4z0iT+KCVP8V0jbn7TatqyN6BK0n9Fvjit6fS1mgIGwUfK0U5bG9oQV6j3GXzfoiX6LyOGNRsY8rH4dvk1Qh894qtY1bGCj2sNsA5DRpwXvY5fIP6UWgbTGJ+gtXDNpdlQl2nT6XlWWgOZmddYukQMQhXrg0LelODPEHrphJBz3Dh2KTw2DNj2f6io1hP3JSnkillPyvAN2RdmRACDXmwE76L1lISh4n8O784s1mZwGLPqpnDS+gQfnxhk2XBn/rUAU4rTAexg==

Now use the decrypt command to decrypt this same piece of ciphertext using the private part of the

key pair, which should recover the original message:

parsec-tool decrypt --key-name my-rsa-enc-key ivk6yCKxFlIXRaQkfI5SrvhJtVXUz2VoXwC2xK7zU6UG1w0LNk7ZScz1pgpghc0IgftjjvhzK+6R4z0iT+KCVP8V0jbn7TatqyN6BK0n9Fvjit6fS1mgIGwUfK0U5bG9oQV6j3GXzfoiX6LyOGNRsY8rH4dvk1Qh894qtY1bGCj2sNsA5DRpwXvY5fIP6UWgbTGJ+gtXDNpdlQl2nT6XlWWgOZmddYukQMQhXrg0LelODPEHrphJBz3Dh2KTw2DNj2f6io1hP3JSnkillPyvAN2RdmRACDXmwE76L1lISh4n8O784s1mZwGLPqpnDS+gQfnxhk2XBn/rUAU4rTAexg==

Output:

[INFO ] Decrypting data with RsaPkcs1v15Crypt...

secret message

You wouldn't normally perform both the encryption and decryption using parsec-tool in this way.

More commonly, the encryption part would be done by an external component using the exported public

key, and only the decryption part would be performed inside Parsec (which has exclusive access to

the private key). This tutorial video shows a similar

demonstration of an RSA encryption workflow using parsec-tool, where the encryption is performed

externally using an online encryption tool.

Generating a Random Number

The Parsec command-line tool can be used to generate random numbers using the entropy facilities provided by the configured back-end provider. Use the following command:

parsec-tool generate-random --nbytes 8

The output will be similar to the following:

[INFO ] Generating 8 random bytes...

[INFO ] Random bytes:

4B 9B FB 11 55 D9 7F 41

Vary the --nbytes argument to generate random sequences of different sizes.

Creating a Certificate Signing Request (CSR)

We can create CSRs using the parsec-tool. Before a CSR can be created, an asymmetric key pair must

exist. In this example, you'll start with a 2048-bit RSA key pair for signing, created as follows:

parsec-tool create-rsa-key --key-name my-rsa-csr-key --for-signing

Once we have a signing key, we can output a CSR using the create-csr command as follows:

parsec-tool create-csr --key-name my-rsa-csr-key --cn my-common-name

This will output an encoded CSR:

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE REQUEST-----

MIICXjCCAUYCAQAwGTEXMBUGA1UEAwwObXktY29tbW9uLW5hbWUwggEiMA0GCSqG

SIb3DQEBAQUAA4IBDwAwggEKAoIBAQC1ijnwCyFk0Q2VjsM6UPtov+oR/Bl8UeEh

/pu+kVnPgMcIumK5QJVBlVEhAFq0lJ4jpXb7no3P0GDbn9tUgpdrS0xp5/OSXHWs

CcZJzWZ9n6zHnFQLQD4Z4LAiVlmfhidF6wNhLihZywn7+aqH5fAOsaFVzIjDElXp

ZGxmd22M5Qqjs0sDuKS1I5+AeedDmlwi+HMNMMaxczgokEbYO3TUSUBX/D1BFUlN

5vv0YTxqir+qzVBYvK47eczEQE0vZhQKZa6Dw4DmDdBQQtob0mQjxXjuYcoj2w9a

XAZZmv+4CJ6K0XZlkr7+CFZgQDMz5B2Mv+gPJU3Mo82qjYGBCXPXAgMBAAGgADAN

BgkqhkiG9w0BAQsFAAOCAQEAG2OyzSuDi/jl0j6WAUaW79ChzZbthzrv03/IiEu9

CLEtXbi8NNwLbwT+zz8fw3/OQnDHfnJ0YAb9WfH3GIdd32TyK1YdqooCyPoQoUzv

crfUrm8sAVRKqD2XU3KRzh+6H6WHnl4ASWfTKdWgvlX4cZ54ztZ52zSHbdHKZmxP

Po3n5Dngxj2GP8nT6tMJsgDG/k7h6//vlgSLChxyDf39ZAXBRJTBGf99Jc8d2Ox3

4EavDuBuXTTDbz5ePz4OLnXCizZSHAZCbPUAcErL/q3vY8zR2O2vo712J2WD1Wdh

I60pltRTP3MAwE554zj/FM6J0Do25B453Rg7H+Pvt1VTUQ==

-----END CERTIFICATE REQUEST-----

The create-csr command allows many components of the Distinguished Name (DN) to be customized,

including the serial number. It is also possible to specify one or more Subject Alternative Names

(SAN) in the CSR. Display the help text for this command as follows:

parsec-tool create-csr --help

Copyright 2022 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Parsec for users

How to use Parsec

On a system where Parsec is installed, it can easily be used with a Parsec Client Library. Those libraries communicate with the Parsec service and integrate with the rest of the software idiomatically.

Parsec Client Libraries are available in the following languages:

- Rust: See examples on how to use the

BasicClient. - C: support exists for using Parsec through the PSA Crypto API for a limited set of primitives. Non-PSA functionality is currently not supported.

- Java: both a native Parsec client, as well as a JCA implementation based on that client.

- Go: work in progress!

- Erlang: native Parsec client with both a high level API and a low level API. The low level API supports all Parsec API calls with protobuf specifications.

Also have a look at parsec-tool, a command-line

client to access Parsec from the terminal.

Please contribute to add more Parsec Client Libraries in the languages that you want!

Building, running and installing Parsec

If you would like to compile and run the Parsec service on your system (if it does not exist), follow these guides:

Copyright 2019 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Parsec for client library developers

This section offers the information needed for building Parsec client libraries. The topics covered are:

- API overview - overview of the API and the design principles behind it

- Wire protocol - detailed description of the representation and meaning of data communicated between the client and service

- Status codes - comprehensive list of response codes returned by the service and their meaning

- Writing a new client library - hints and tips for getting started with developing a new client library

- Operations - structured description of all Parsec operations; this subsection provides the official documentation for the API

Copyright 2019 Contributors to the Parsec project.

API Overview

Introduction

This document introduces the API contract that exists between the client and the service, covering its general principles and organization. Use this document in combination with the wire protocol specification and the operation directory as a reference guide for the development of client libraries.

Audience

This document details the API that is exposed directly by the service to its clients. This is the API that is invoked over the IPC transport between the client process and the service. Client applications do not consume this API directly. Instead, they consume a client library in their chosen programming language. The client library will present an idiomatic and simplified view of the API, making heavy use of argument defaulting to shield application developers from much of the complexity of invoking cryptographic operations. Client libraries should present the API in a form that is "easy to use and hard to get wrong". The audience for this document is the client library developer, not the application developer. Application developers should consult the client library documentation package instead.

Opcodes and Contracts

The API is expressed as a set of individual and distinct operations. Each operation has a unique numerical opcode to set it apart from other operations, and to allow for it to be unambiguously selected for in a client request. (See the wire protocol specification for information about how the client must structure such requests). Each operation also has an input contract, which defines the arguments that the client must supply when invoking it. It also has an output contract, which defines the operation results that the client can expect to receive from the service upon completion. In current manifestations of the API, all input and output contracts are defined as protobuf messages, which provides a strong contractual definition and good interoperability with multiple programming languages.

All operations are catalogued in the operation directory. There is a separate documentation page for each operation, which will specify the correct opcode to use, and will provide links to the input and output contracts.

In order to make an API call, the client must use the wire protocol specification to form a valid request to the service. The request header must contain the opcode of the operation being performed, and the request body must contain serialized data bytes conforming to that operation's input contract. The service will execute the operation, and form a response according to the wire protocol. The response will contain serialized data bytes conforming to the operation's output contract.

Selecting Providers

All of the operations in the API are implemented by back-end modules known as providers. A provider is a module that is capable of implementing operations by making use of available platform hardware or services. For example, if cryptographic services are supplied by a hardware secure element of some kind, then there would be a provider for that secure element. There may be a different provider for a software-only solution. And so forth. It is valid for these different providers to co-reside within the service. The availability of providers is governed by configuration that is applied at service-deployment time.

While the service can be composed from multiple providers, any given API operation needs to be implemented by a single provider. This means that client code needs to specify the target provider when it makes an operation request. To achieve this, the service assigns an 8-bit integer value (from 0 to 255) to each available provider. In practice, the number of providers would be very small: probably just two or three. This integer value is the provider identifier. Client code must set a single provider identifier in each API request. The wire protocol specification explains how a request header field is used to route the request to the correct provider.

In order to set a provider identifier in an API request, the client must first be able to determine

what providers are available, what their identifiers are, and what their characteristics are (such

as whether they are hardware-backed or software-backed). This is done by first referencing the

core provider. The core provider is the only provider that is guaranteed to be available in any

deployment of the service. It has a provider identifier of zero (0x00, the only reserved value for

provider identifiers). The core provider is special in that it doesn't implement any security or

cryptographic operations. The core provider is used to represent the service as a whole. The

operations of the core provider can be used to gather information about the health and configuration

of the service. It can be used to ping the service to check whether it is responsive, and to check

the highest version of the wire protocol that it supports. The core provider can also be used to get

information about the cryptographic providers, their characteristics and their 8-bit identifier

values. Based on this information, the client can determine which provider is best suited to its

requirements. It can then use the integer identifier of that provider to make API requests.

The expected pattern is that a client would determine a single provider that best suits its needs, and then use that provider exclusively for all cryptographic operations. While this usage would be considered typical, it is certainly not enforced. There is nothing to prevent a client from using different providers for different operations if it so desires. In many deployments, it is possible that only a single cryptographic provider would be available anyway. To determine the best available or most suitable provider, a client application can use the capability check mechanism, described below.

Open-Closed Principle

The API is designed to evolve over time. This evolution will be governed by the open-closed principle. In practice, this means that each operation in the API, once introduced, will not be contractually modified. The API can only change by introducing new operations. This preserves backwards compatibility with client code. Any client code that makes use of any given operation will continue to work, even if new operations are introduced.

Non-breaking changes

In some cases, it might be helpful to update contracts in a non-breaking way. If multiple operations share the same parameters (such as the PSA algorithm or key attributes), this avoids having to duplicate all of them if an update is done to those parameters. To make sure that backward compatibility with client code is always preserved and that the Parsec service remains stable through updates, the allowed changes are restricted to the following:

- Adding a new optional field to an existing type. If not set, the contract containing the new field should behave exactly the same as the version without it. The new field should be ignored if not recognized by an old version. That means that the functionality brought by a new optional field might not be exercised if the service is older than the client, without an error returned.

- Adding a new variant to an existing enumerated type. If not recognized during deserialization, the

InvalidEncodingerror should be returned.

In the future, capabilities discovery operations might be added to give a way for clients to check what parameters are supported. See the history of this feature here.

Deprecation

While the open-closed principle dictates that operations will not be contractually changed once they have been introduced, it may sometimes be necessary to deprecate specific operations. This will often be to encourage the use of a new operation with an improved feature set and a different contract. Deprecation is largely a documentation exercise: the operation directory will indicate when an operation has been deprecated. This does not mean that the operation will no longer work. It simply means that any new use of the operation is strongly discouraged in favor of a better alternative.

Capability Checks

The API includes a capability check operation, which allows the client to determine the set of operations that are available. There are two reasons why the client needs this capability check:

- The API can evolve over time, introducing new operations with new opcodes. In general, a client cannot know whether it is talking to a service that supports these newer operations, so it needs to check the level of support in advance.

- Different cryptographic providers have different capabilities. An operation that is supported in one provider might not be supported in another.

Refer to the operation directory for information on how to perform a capability check.

Application Identity

Every client application that uses the API must present an application identity. Application identities are arbitrary byte strings, which are used by the service to isolate the activities of one client from those of another. The storage of secure assets such as keys is segregated on a per-client basis: assets created by one client cannot be accessed by another. The service always uses the client's application identity string to maintain this separation.

The means by which application identities are generated or assigned is outside of the scope of this specification. The only requirements for application identities is that they must be unique and stable. This means that any given application identity string can be used to identify one and only one client application. It also means that the application identity string for any given client should remain the same over time, even across system resets.

The granularity of application identities is not defined. In particular, there is no assumption that a client application corresponds precisely with a single client process. A client application might be composed of multiple processes. Conversely, a single process might contain multiple distinct client applications. Client applications might also be organized into isolated environments such as containers. Provided that client application is able to present a unique and stable identity string for each API call, it does not matter how they are structured and deployed.

Authentication and Sessions

Clients present their identity strings to the service on each API call. As set out in the wire protocol specification, they do this using the authentication field of the API request.

There are currently three ways in which the client can use the authentication field to share its identity with the service:

- direct authentication.

- authentication tokens.

- Unix peer credentials.

With direct authentication, the client authenticates the request by directly copying the application identity string into the authentication field of the request.

With authentication tokens, the client obtains a token from an identity provider and sends it as the authentication field of the request. The token is reusable for a specified duration of time, after which a new one must be issued. The application identity is contained in the token and can be extracted by the service after verifying the authenticity of the token. A more detailed description of authentication tokens and their lifecycle is present in the sytem architecture specification.

With Unix peer credentials, the client authenticates by self-declaring its Unix user identifier (UID) inside the authentication field of the request. The Parsec service verifies that this self-declared UID matches the actual UID of the connecting process via the Unix peer credentials mechanism.

When it makes an API request, the client needs to tell the server which kind of authentication is being used. This is so that the server knows how to interpret the bytes in the authentication field of the request. As described in the wire protocol specification, the client does this by setting an integer value in the auth type field of the request header. The permitted numerical values for this field are given as follows:-

- A value of 0 (

0x00) indicates that there is no authentication. The service will not expect any content in the authentication field of the request. If any authentication bytes are present, they will be ignored, but the request will still be considered valid. (For clients, it is considered bad practice to supply a non-empty authentication field in this case, because it is contradictory to supply authentication material while indicating an unauthenticated call, and it indicates improper coding or a possible defect on the client side). See the section below on unauthenticated operations. - A value of 1 (

0x01) indicates direct authentication. The service will expect the authentication field to contain a cleartext copy of the application identity, encoded as a UTF-8 string. - A value of 2 (

0x02) indicates authentication tokens. This authentication type is not currently supported. The service will expect the authentication field to contain a JWT token. Tokens must be signed with the private key of the identity provider and their validity period must cover the moment when the check is done. - A value of 3 (

0x03) indicates Unix peer credentials authentication. The service expects the authentication field to contain the Unix user identifier (UID, not username) of the connecting process as a zero-padded little-endian 32-bit unsigned integer. The Parsec service will verify that this self-declared UID is consistent with the UID from the Unix peer credentials. - A value of 4 (

0x04) indicates authentication through JWT SPIFFE Verifiable Identity Document. The service expects the authentication field to contain a JWT-SVID token as described in the SPIFFE standard. The token must be encoded using the JWS Compact Serialization. The service will use the SPIFFE ID validated from the SVID as application identity.

Other values are unsupported and will be rejected by the service. See the authenticators page for more details.

Unauthenticated Operations

Authentication via the application identity is only needed for cryptographic operations. Core

provider operations do not require authentication. Core provider operations include those that are

used to ping the service and gather information about its capabilities. These operations neither

require nor support any notion of per-client isolation. Consequently, they can be called without any

authentication. For requests to the core provider, the auth type header field should always be

set to 0 (0x00).

Content Type and Accept Type

As per the wire protocol specification, API request headers contain fields

for content type and accept type, which respectively indicate how the request body and

response body are encoded. Currently, the only supported value for these fields is one (0x01),

meaning that all request and response bodies contain serialized protobuf messages. All other values

are unsupported and will be rejected by the service.

PSA Crypto Operations

The majority of the operations in this API are derived from the PSA Crypto API Specification. There is a near one-to-one correspondence of functional operations between the two APIs. The main difference is that the PSA Crypto API is defined in the C programming language, whereas the API described here is language-agnostic. There is otherwise a close contractual equivalence between the two, and this is intentional.

In the operation directory, operations derived from the PSA Crypto API have symbolic names that start with the Psa prefix, and their numerical opcodes are all in the 1,000-1,999 (decimal) range. Opcode ranges are an important aspect of the API design because they form the basis of an extensibility mechanism. In the future, it will be possible for contributors to partition the numerical opcode space with ranges for custom operations.

Key Names, Enumerating and Referencing

While this API is closely aligned with the PSA Crypto API, there are some differences. One important difference is in the conventions used to name and reference cryptographic keys.

In the PSA Crypto API, every key has a 32-bit numerical identifier. This identifier is set by the caller when the persistent key is created. Client code then uses this 32-bit identifier to refer to the key for use in any cryptographic operation.

This API is different: the key names are not 32-bit numerical values, they are UTF-8 strings. Cryptographic operations are all specified in terms of the key name string. It is important to understand that the opacity of keys - one of the critical design characteristics of the PSA Crypto API - is preserved here. Key names are used to reference keys for cryptographic operations, but the actual key material is never exposed to the caller of the API unless an explicit operation is invoked to export the key (and the key's usage policy permits for such an export to occur).

The use of string names offers greater flexibility in how names can be chosen and structured. It allows for names to be readable and meaningful. It also allows for names to follow a structured pattern with separators, similar to a file path. This allows keys to not only be named in meaningful ways, but also for them to be organized according to a meaningful structure, just like files on a file system. Keys with a similar purpose, for example, can be stored in the same part of the notional "tree".

Key names adopt a path structure similar to Unix file paths, such as /keys/rsa/my_key_1.

This key naming convention permits for the API to support key enumeration, where the client is

able to determine the set of known keys according to some wildcard pattern such as /keys/rsa/*.

All key names are implicitly in a per-client namespace, so it is impossible for one client application to enumerate or otherwise discover the keys that are owned by another client application.

Providers can impose length restrictions on key names to help with internal storage and argument validation. This API reference does not define any single fixed maximum length. Clients must determine the maximum length at runtime using the capability checking mechanism.

Service discovery

Establishing a connection between the client and the service requires common understanding of the

communication mechanism and the address at which the service can be found. While the default

mechanism is through a Unix domain socket found at /run/parsec/parsec.sock, that can be easily

changed by an admin for various reasons. Clients must therefore be made aware of such changes and

the defined mechanism for this uses environment variables.

The PARSEC_SERVICE_ENDPOINT environment variable is the preferred method of indicating to a

process where to find the communication channel for the Parsec service. The variable should contain

a URI as defined in RFC3986 - for example, for the default

domain socket location, the URI would be unix:/run/parsec/parsec.sock. Client libraries must be

capable of scanning for the environment variable, parsing it, and bootstrapping communication using

the URI, with no input from the client application. The libraries must also allow the application to

override these settings.

Full API Reference

For the full reference guide to individual API operations, please refer to the operation directory.

Copyright 2019 Contributors to the Parsec project.

Wire Protocol

Introduction

This document describes and specifies the wire protocol that exists between the service and its clients. It explains the general principles of how the protocol is structured, and goes on to provide a full specification that can be used as the basis of both client-side and service-side code.

Scope

This document describes the principles, patterns and low-level details of the wire protocol. This covers the details that are common to all messages that pass between the service and its clients. This document is not an API specification for the service. Individual API operations, along with their behaviors, inputs and outputs are described separately in the API specification. The wire protocol is the underlying message-passing mechanism that enables the API.

Audience

A thorough understanding of the wire protocol is necessary if you are developing new capabilities within certain parts of the service, or if you are developing or extending one of its client libraries. However, it is not necessary to understand the wire protocol in order to consume the client API into an application.

General Principles

Binary Protocol

The wire protocol is a binary and stream-oriented protocol. It is designed for speed and compactness of transmission.

Requests and Responses

The wire protocol is principally structured around the notion of a request and a response. Requests and responses are self-contained pairs of entities, where each request is answered by exactly one response. Requests always travel from the client to the service, and responses always travel back from the service to the client. Each pair of request and response encapsulates a single call to a single operation provided by the service. Client library code is concerned with forming requests and transmitting them to the service. Service code is concerned with processing requests, forming responses, and transmitting those responses back to the client. The term message is used to refer generically to requests and responses in contexts where there is no need to draw a distinction between them.

Analogy With HTTP and REST

The request-response pattern of the wire protocol is intentionally modeled on the familiar notion of calling a REST API over HTTP. In fact, one of the guiding principles of the wire protocol design has been to create something that might loosely be called a "lightweight REST". This term must be applied with caution, however. REST is a collection of architectural principles, not a protocol. It does not follow that all of the RESTful principles are adopted here. However, thinking of the wire protocol as being like a web service protocol, only without any dependency on HTTP or similar stacks, can be a good way to gain an initial understanding. Some patterns of the wire protocol design have their foundation in a mixture of concepts taken from HTTP and REST, but the wire protocol itself is neither of these things: it is an entirely bespoke protocol.

Synchronous Operation

The wire protocol is based on requests and responses, and therefore models synchronous patterns of interaction. There is nothing in current versions of the protocol to assist with asynchronous patterns of interaction between the client and the service. Future versions of the protocol may introduce such concepts. In the meantime, depending on the type of transport used, it may be possible for the service or the clients to take advantage of asynchronous features of the transport (such as the non-blocking mode of a socket) to provide certain levels of asynchronous control.

Separation of Protocol and Transport

The wire protocol defines the format of messages, and some key characteristics and invariants concerning their transmission between the service and its clients. It does not mandate a specific transport stack. The wire protocol is a binary, stream-oriented protocol. As such, it can be carried by any transport medium that supports the reliable transmission of binary octet streams, such as Unix domain sockets (connected in streaming mode) or TCP sockets. Datagram-oriented transports are not supported, because the protocol depends on the reliable transmission of entire messages in the proper sequence.

Separation of Header and Body

Every message (whether request or response) has a header and a body. Again, this is conceptually similar to the separation of header and body in HTTP. And, like HTTP, this protocol allows some flexibility in how the body content is encoded. The wire protocol borrows HTTP's notion of the content-type and accept header fields, which allow the client to tell the server how to interpret the content, and also to declare what kind of response is acceptable in return. The only difference is that the wire protocol uses numerical byte fields to indicate these values, where HTTP uses string key-value pairs and media types. This is another illustration of how the wire protocol can be viewed as a more compact and stripped-down HTTP.

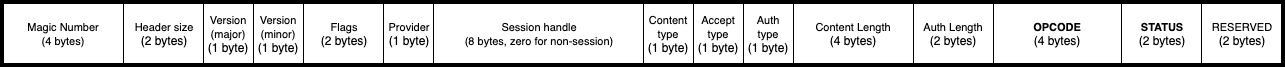

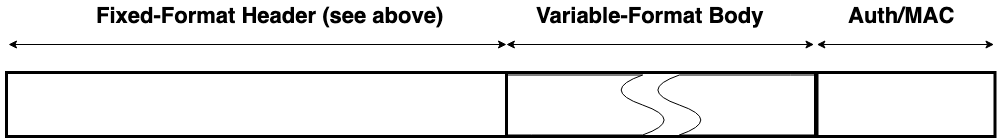

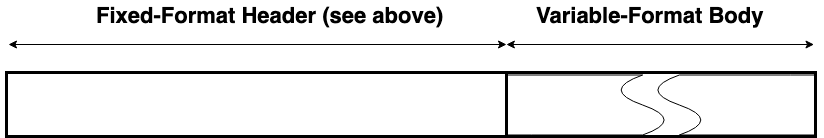

The message headers are fixed-length and fixed-format. The headers themselves have no variability in their encoding, nor do they adhere to any encoding or serialization standard. The format of the header is defined solely by this specification. When writing code to either transmit or receive a header, the code must be written and validated according to this specification alone. Headers are composed of a series of single-byte and multi-byte fields.